Developers and Lawyers Use a Legal Maneuver to Strip Black Families of Land

By Todd Lewan and Dolores Barclay

The Associated Press

Part Three of a series. Part 1 available in The Authentic Voice.

Ivene Sanders, 72, and his niece, Eldessa Johnson, 50, at Johnson’s home in Southfield, Mich., Aug. 23, 2001. The Sanders lost 300 acres of farmland, in their family for 83 years, at a 1998 partition sale. (Photo: Carlos Osorio/AP)

Lawyers and real estate traders are stripping Americans of their ancestral land today, simply by following the law.

It is done through a court procedure that is intended to help resolve land disputes but is being used to pry land from people who do not want to sell.

Black families are especially vulnerable to it. The Becketts, for example, lost a 335-acre farm in Jasper County, S.C., that had been in their family since 1873. And the Sanders clan watched helplessly as a timber company recently acquired 300 acres in Pickens County, Ala., that had been in their family since 1919.

The procedure is called partitioning, and this is how it works:

Whenever a landowner dies without a will, the heirs — usually spouse and children — inherit the estate. They own the land in common, with no one person owning a specific part of it. If more family members die without wills, things can get messy within a couple of generations, with dozens of relatives owning the land in common.

Anyone can buy an interest in one of these family estates; all it takes is a single heir willing to sell. And anyone who owns a share, no matter how small, can go to a judge and request that the entire property be sold at auction.

Some land traders seek out such estates and buy small shares with the intention of forcing auctions. Family members seldom have enough money to compete, even when the high bid is less than market value.

“Imagine buying one share of Coca-Cola, and being able to go to court and demand a sale of the entire company,” said Thomas Mitchell, a University of Wisconsin law professor who has studied partitioning. “That’s what’s going on here.”

This can happen to anyone who owns land in common with others; laws allowing partition sales exist in every state.However, government and university studies show black landowners in the South are especially vulnerable because up to 83 percent of them do not leave wills — perhaps because rural blacks often lack equal access to the legal system.

Mitchell and others who have studied black land ownership estimate that thousands of black families have lost mililions of acres through partition sales in the last 30 years.

“It’s the all-time, slam-dunk method of separating blacks and their land,” said Jerry Pennick, a regional coordinator for the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, which provides technical and legal support to black farmers.

By the end of the 1960s, civil rights legislation and social change had curbed the intimidation and violence that had driven many blacks from their land over the previous 100 years. Nevertheless, black land loss did not stop.

Alvie Marsh’s scarred and knotted hands betray a life of hard work, on May 10, 2001, at his home in Choudrant, La. Marsh’s family lost 80 acres in the 1950s when a white oil man acquired the property in a questionable partition sale. (Photo: Rogelio Solis/AP)

Since 1969, the decline has been particularly steep. Black Americans have lost 80 percent of the 5.5 million acres of farmland they owned in the South 32 years ago, according to the U.S. Agricultural Census. Partition sales, Pennick estimates, account for half of those losses. A judge is not required to order a partition sale just because someone requests it. Often, there are other options.When the property is large enough for each owner to be given a useful parcel, it can be fairly divided. When those who want to keep the land outnumber those who want to sell, the court can help the majority arrange to buy out the minority. In at least one state, Alabama, the law gives family members first rights to buy out anyone who wants to sell.

Yet, government and university studies show, alternatives to partition sales are rarely considered. When partition sales are requested, judges nearly always order them.

“Judges order partition sales because it’s easy,” said Jess Dukeminier, an emeritus professor of law at the University of California at Los Angeles. Appraising and dividing property takes time and effort, he said.

Partition statutes exist for a reason: to help families resolve impossible tangles that can develop when land is passed down through several generations without wills.

In Rankin County, Miss., for example, the 66 heirs to an 80-acre black family estate could not agree on what to do with the land. One family member, whose portion was the size of a house lot, wanted her share separated from the estate. Three other heirs, who owned shares the size of parking spaces, opposed dividing the land because what they owned would have become worthless. So, in 1979, the court ordered the land sold and the proceeds divided.

Even when the process works as intended, it contributes to the decline in black-owned land; the property nearly always ends up in the hands of white developers or corporations. The Rankin County land was bought at auction by a timber company.

But the process doesn’t always work as intended. Land traders who buy shares of estates with the intention of forcing partition sales are abusing the law, according to a 1985 Commerce Department study.

The practice is legal but “clearly unscrupulous,” declared the study, which was conducted for the department by the Emergency Land Fund, a nonprofit group that helped Southern blacks retain threatened land in the 1970s and ’80s.

Blacks have lost land through partitioning for decades; the AP found several cases in the 1950s. But in recent years, it has become big business. Legal fees for bringing partition actions can be high — often 20 percent of the proceeds from the land sales. Families, in effect, end up paying the fees of the lawyers who separate them from their land.

Moreover, black landowners cannot always count on their own lawyers. Sometimes, the Commerce Department study found, attorneys representing blacks filed partition actions that were against their clients’ interests. The AP found several cases in which black landowners, unfamiliar with property law, inadvertently set partition actions in motion by signing legal papers they did not understand. Once the partition actions began, the landowners found themselves powerless to stop them.

The Associated Press studied 14 partition cases in detail, reviewing lawsuit files and interviewing participants. The cases stretched across Southern and border states.

Each case was different, each complicated with some taking years to resolve. In nearly every case, the partition action was initiated by a land trader or lawyer rather than a family member. In most cases, land traders bought small shares of black family estates, sometimes from heirs who were elderly, mentally disabled or in prison, and then sought partition sales.

All 14 estates were acquired from black families by whites or corporations, usually at bargain prices.

Migrations that have scattered black families increase their vulnerability to partition actions. Historians say those who fled the South seldom spoke of the lives they left behind. Their descendants may not realize they have inherited small shares of family property and have no attachment to the land. All a land trader has to do is find one of them.

Some families have hired attorneys and tried to fight back. However, said Mitchell, the Wisconsin law professor, “the families nearly always lost.”

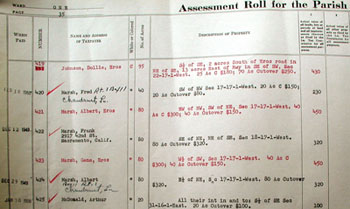

A 1949 tax assessment roll of black landowners in Jackson Parish, La., that shows Albert Marsh of Choudrant, La., was the owner of a total of 160 acres at that time. (Courtesy: Jackson Parish, La., Courthouse)

To understand how partition sales work in practice, it is useful to begin with a relatively simple one. The case of the Marsh family of Northern Louisiana contains the three typical elements: land passed down without wills, black landowners unfamiliar with property law and a white businessman who saw an opportunity and took it. But it has few of the complications that can make partition cases difficult to follow.

Louis Marsh, a freed slave, accumulated 560 acres in Jackson Parish in the decades after the Civil War. When he died without a will in 1906, his children inherited the land. They owned it in common until 1944, when they asked the court to divide it.

The court gave six siblings 80 acres each, court records show. The final 80 acres would have gone to their brother, Kern Marsh, but he had fled Louisiana after killing a man. So, the court decided, Louis Marsh’s children would continue to own that share in common.

With the family’s permission, one of the siblings, Albert Marsh, farmed those extra 80 acres along with his own share. As 20 years passed with no sign of Kern Marsh, the family came to think of all 160 of those acres as Albert Marsh’s land. Family members said they expected it would be passed down to Albert’s children when he died. That’s not what happened.

On April 11, 1955, about the time oil rigs were appearing on neighboring property, Albert Marsh died without a will. Not long after, a white oil man named J.B. Holstead purchased an 11.4-acre interest in the extra 80 acres. The seller was one of Albert Marsh’s nephews, Leon Elmore, who has since died.

The deed, filed on Aug. 13, 1955, says Elmore was paid $100 cash and other consideration — a used truck, according to Elmore’s son, Leon, Jr.

Three days later, Holstead filed for a partition sale of the 80 acres. Six days after that, a judge sorted out who owned shares in the 80 acres.

Because the 1944 partition had left that land as common property of Louis Marsh’s children, the true owners were his 23 living descendants, the judge decided. Leon Elmore was among them, giving him the right to sell his share to Holstead.

The Marshes did not understand what was happening and did not have a lawyer, said Albert Marsh’s son, Alvie, 86. Besides, he said, challenging a white businessman in the 1950s “never entered your mind — ‘less you wanted the rope.”

On Nov. 15, 1955, the same judge granted Holstead’s request for a partition sale. Court costs, plus a $250 fee to Holstead’s lawyer, were to be paid from the proceeds.

At the Jan. 21, 1956, auction, Holstead bought the 80 acres for $6,400. He quickly sold the land and the oil and gas rights for unspecified amounts, records show.

The land changed hands several times before being acquired in 1996 by Willamette Industries Inc., a wood-products company. A company spokeswoman said Willamette was unaware of the land’s history.

Holstead is dead; his son, John Holstead, a Houston lawyer, said he was unaware of the case. When it was described to him, he said: “All of the legal procedures of Louisiana law were followed.”

Alvie Marsh believes the land was taken unfairly. “I’ve lived with that for 45 years,” he said. Today, he lives in a shack on that part of the estate his family was able to keep.

Things were more complicated when a South Carolina real estate trader went after two tracts owned by different branches of the Beckett family in the 1990s.

In 1990, Audrey Moffitt sought a 335-acre estate in Jasper County, S.C., that had been owned by the family since 1873.

Frances Beckett, a 74-year-old widow with a fourth-grade education, was one of 76 heirs to the estate. According to court papers, she was bedridden with cancer; her doctor had given her three months to live.

The dying woman accepted Moffitt’s offer of $750 for her 1/72 interest — worth $4,653, according to a subsequent appraisal by J. Edward Gay, a real estate consultant. An appeals court would later call it the only “true” appraisal of the property.

Moffitt then bought out six other heirs for a total of $6,600, court papers show. Among them, she paid Edward Stewart, 88, a man with no formal education, and Flemon Woods, 80, with a third-grade education, a combined $5,800 for their one-sixth interest. It was worth $55,833, according to Gay’s appraisal.

Moffitt filed her partition action in January 1991. Beckett family members countersued, alleging Moffitt had secured the elderly heirs’ signatures without the presence of a notary. A special referee in the Court of Common Pleas ruled that the estate be sold.

The property was broken into two pieces that were auctioned separately. Fifty acres were purchased for $75,000 at at December 1991 sale by John Rhodes, a real estate broker from nearby Estill, and his mother, Florence. Of this, $12,864 went to Moffitt for her shares and nearly $20,000 was taken for court costs, leaving $42,331 for the family.

Today, Rhodes and his siblings own the tract, which is assessed at $200,000.

Moffitt bought the remaining 285 acres for $146,000 in February 1992. (That included $24,338 she paid to herself for her own shares.)

Lewis Cook of Carrollton, Ala., sits across the street from the Pickens County Courthouse on Aug. 22, 2001. The courthouse, typical in the South, houses most of the local property records, including those of the Sanders family. (Photo credit: Dave Martin/AP)

Two years later, however, an appeals court ruled that the signatures of the elderly Beckett heirs were obtained illegally. The court also cited uncontested evidence that Moffitt or her partner had led Edward Stewart to believe he was selling a right of way, led Frances Beckett to believe she was selling timber rights and led Flemon Woods to believe he would be liable for substantial back taxes if he did not sell.

The court characterized Moffitt’s dealings with the three elderly family members as “unconscionable.” When Moffitt paid an additional $45,075 for the shares, however, the court validated the partition sale.

With the additional payment, Moffitt’s outlay for the land totaled $198,425, court papers show. Deduct the $37,202 she received from the partition sales for her own shares of the estate, and her true outlay was $161,223.

Moffitt has since broken up the property and resold it to a locally prominent family and several area businesses, property records show. In one transaction, she swapped part of the old Beckett land for an adjoining piece of property, which she then sold.

Her proceeds from these sales, property records show, total $1,708.117 — nearly 11 times what she paid for the property.

“They basically just ran these people out,” said Bernard Wilburn, an Ohio lawyer who represented several Beckett heirs. This wasn’t the only time the Becketts encountered Moffitt.

In 1991, she paid heirs on another side of the family $2,775 for a one-fifth interest in 50 acres of undeveloped land along State Highway 170 in Beaufort County, S.C. — the main link between Savannah, Ga., and the resort island of Hilton Head. The following year, Moffitt filed for partition, forcing the 42 heirs into court.

The family knew what was coming because of what was happening to their relatives, so they negotiated a settlement. They allowed Moffitt to pick out a beset 10.4 acres of the estate in return for dropping the partition action.

Moffitt didn’t keep the land long. Records show that in October 1998, the state paid her $17,000 for a roadway easement of less than an acre. In January 1999, she sold the rest to a Methodist church for $200,000.

In all, she received $217,000 for land she had purchased for $2,775.

“You can’t buck these big-money developers,” said family member William Jackson, a retired math teacher. “You are most times forced to settle for less than what your property is worth.”

Moffitt, of Varnville, S.C., did not return phone calls but replied in writing to a letter requesting comment. Apparently limiting her remarks to the larger Beckett property, she defended the dealings described as “unconscionable” by the court, calling her payments to the elderly Becketts “fair value.”

She characterized the Beckett ownership as “a convoluted mess” that made the land unmarketable. She added: “The heirs could have done for themselves what I did, but for generations had not done so. It is difficult sometimes to get two people to agree; getting 30 or 40 or more people all to agree to sell or keep and use their property would be virtually impossible, in my experience.”

More complicated still is the story of the Sanders estate in Pickens County, Ala.M.L. Wheat of Millport, Ala., wanted to buy the 300 acres of timberland that had been in the Sanders family for 83 years. In early 1996, he talked price with one of the owners, Ivene Sanders. They met in the office of Wheat’s lawyer, William D. King IV.

When Wheat learned that buying the land would require reaching agreement with about 100 heirs, he backed away from the deal.

Then, in May of that year, the story took a turn. King, who had represented Wheat, filed a partition action on behalf of 35 members of the Sanders family, naming other heirs as defendants.

Only two family members signed the complaint seeking the sale: Ivene Sanders, now 72, Archie Sanders, now 75, with a third-grade education. Court papers show both later insisted they did not understand what they were signing. Ivene Sanders told the AP he thought he was authorizing King to determine the size of each family member’s share.

Several family members King listed as plaintiffs turned out not to own shares. All but five of the plaintiffs who did own shares joined Ivene and Archie Sanders in filing papers stating that they had not authorized King to pursue the partition action.

Several hired another lawyer to try to stop the sale.

The AP could find nothing in the record indicating the wishes of the other five plaintiffs. One, Emma Jeann Sanders, told the AP she had never hired King. Another, Lillie Velma Gregory, was too ill to be interviewed, but her daughter, Fentris Miller Hayes, said her mother had not hired King. Another is now dead. The other two could not be located.

Whose interest was King representing as he pursued the partition action for more than two years? King would not comment beyond saying that the record speaks for itself.

As the case went on, the number of family members being sued to force the sale reached 78. Of these, 18 did not object to the sale, according to the judge. In fact, in the case’s final year, the judge decided that seven of them were no longer defendants, but plaintiffs.

Five of those seven then filed objections to the sale, too.

Family members who took a position on the sale — plaintiffs and defendants alike — were overwhelmingly opposed, court records show. Some said they never wanted the family land sold. Others, including Ivene and Archie Sanders, said that if they were to sell, they would want to do so privately rather than risk a low winning bid at a court-ordered auction.

Nevertheless, Circuit Court Judge James Moore ordered an auction. The Melrose Timber Co., Inc., bought the property on Nov. 24, 1998, for $505,000, court papers show.

It was not a bad price, but the family did not get all the money. King collected $104,730 in fees and expenses — about 20 percent of the sale proceeds.

After court costs were deducted, $389,170 remained to be divided among 96 heirs, some of whom incurred thousands of dollars in legal fees fighting the sale.

Some family members wanted to appeal but decided they could not afford the legal fees, said Ivene Sanders’ niece, Eldessa Johnson, 50, of Southfield, Mich.

King, reached at his office in Carrollton, Ala., said: “I have no additional comments, other than what is in the record. … I have nothing to hide. This case has been well litigated.”

Moore said partitioning laws, intended to protect landowners, are often used against them and may need revision. However, he said, once the partition request was filed, he approved it largely as a matter of routine.

In his three-country rural circuit, he said, two or three such cases are going on all the time. Most, he said, involve black families.

EDITOR’S NOTE — Associated Press Writer Allen G. Breed, Shelia Hardwell Byrd and Deborah Bulkeley and Investigative Researcher Randy Herschaft contributed to this story.

Next StoryReturn to Series: Torn from the LandMore Stories: The Authentic Voice

For More Information

Torn from the Land is characterized by strong research, attention to detail, sound historical context, and compelling quotes. Central to the series’ power is the meticulous investigative reporting of AP reporters Dolores Barclay and Todd Lewan and the decision of editor Bruce DeSilva to allow into the stories only cases that could be proven beyond doubt. The story creates a fresh awareness about the history of African Americans and their descendants.

Torn from the Land is characterized by strong research, attention to detail, sound historical context, and compelling quotes. Central to the series’ power is the meticulous investigative reporting of AP reporters Dolores Barclay and Todd Lewan and the decision of editor Bruce DeSilva to allow into the stories only cases that could be proven beyond doubt. The story creates a fresh awareness about the history of African Americans and their descendants.

Teacher’s Guide: Torn from the Land