Torn From The Land, The Associated Press

Dolores Barclay and Todd Lewan of the Associated Press begin their series with this telling passage: “For generations, black families passed down the tales in uneasy whispers: ‘They stole our land.’” From there, the series traces the tumultuous, sometimes violent journey of property ownership, theft, and swindles and reveals some of the reasons for the muted voices.

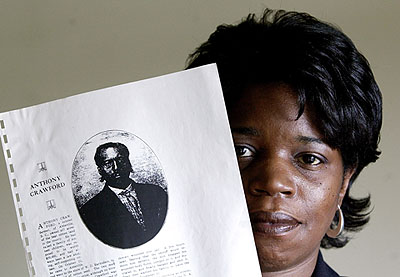

Doria Dee Johnson holds up a picture of her great-great-grandfather, Anthony P. Crawford, April 10, 2001. (Photo credit: Kenneth Lambert/AP)

Torn from the Land is characterized by strong research, attention to detail, sound historical context, and compelling quotes. Central to the series’ power is the meticulous investigative reporting of the AP reporters and the decision of editor Bruce DeSilva to allow into the stories only cases that could be proven beyond doubt (Text: pp. 204, 208; DVD: AP Team interview, 1:52). The cases that met DeSilva’s standard come alive in the series through the voices of the people whose land was taken.

Including context, DeSilva says, was particularly important throughout the series, helping readers understand why events unfolded as they did decades ago and why they resonate so profoundly today (DVD: AP Team interview, 9:42). Equally important was the team’s ability to accommodate the complexity at the heart of many cases, where some current landowners held property once stolen through murder (DVD: AP Team interview, 6:09). The reporters worked to paint a fair and complete picture of the people who had nothing to do with taking the property but now own misbegotten land (DVD: AP Team interview, 4:37).

The choice not to present images of the people responsible for taking the land—whether modern-day or long dead—left out a significant part of the visual story being told. It would be instructive for students and professionals to tackle Barclay’s question on the matter (DVD: AP Team interview, 13:06): “Would it make the story more powerful to have to the face of the deputy sheriff who led a mob into a jail. . . . Would that make readers understand the story more; care more . . . ?”

In the Classroom

Listen to the AP reporters talk about the challenge of getting information from reticent record keepers in small towns, and you hear the journalists’ suspicion that they faced a strain of intimidation as old and corrupt as the cases they were investigating (Text: p. 205; DVD: AP Team interview, 2:56).

Explore with students the journalists’ safety concerns and the conclusions Barclay and Lewan seemed to reach that many of the conflicts they experienced and the reporting challenges they encountered were grounded in racism. Push students to talk about the ways journalists can get beyond the obstacles faced by the reporters—fear, inertia, and bigotry included—to tell these important stories.

Ethics: Portraying People Fairly

Stories about prejudice and racism, often driven by egregious offenses and unsympathetic characters, can test a journalist’s resolve to cover people fairly. But the credibility of the story is only strengthened when all sources are treated fairly and respectfully. Readers, listeners, and viewers learn more and have more on which to base their judgments and decisions when sources are given the chance to be heard fully.

Embrace complexity—Recognize at the outset that no single action or remark is the sum of a person’s character. Actively seek out competing truths about sources, especially when they stand accused of prejudice or racism. Include that complexity in the story.

Avoid guilt by association—Recognize that it’s very easy for the audience to assume that all characters in a story who share a race or ethnicity are guilty of racism, though that’s true for only a few. Be specific in storytelling when identifying those who’ve committed acts of prejudice or bigotry. Pay attention to how words and images are juxtaposed—in headlines, teases, captions, or graphics—so that you don’t inadvertently impugn a source’s integrity (Text: pp. 305–306; DVD: Yeh interview, 7:59).

Share quotes and scripts—A reporter need not relinquish control of a story to give sources access to their words. Read controversial quotes back to sources or summarize what they say; give people a chance to read relevant parts of a story’s script before it airs. This offers them a chance to add to what they’ve said or enrich the context in which they intended their remarks. Journalists can still choose how to handle that information (Text: pp. 45-46; DVD: Ojito interview, 8:59).

Also in the DVD Topic Index

Assignments

2. Examine the ways the AP reporters identified people by race in the stories. Write an essay analyzing the different forms of racial identification you found. Consider in your analysis Dolores Barclay’s statement that there’s a way to “humanize a people more” with the way you use racial identification (DVD: AP Team interview, 8:34).

3. Editor Bruce DeSilva insisted that the Torn from the Land reporters weave information about the reporting process into their writing. “The more [readers] know about how we go about our business, the more they’ll understand it, the more they’ll trust us,” he says (DVD: AP Team interview, 2:03). Write an essay on the value—or drawback—of making your reporting technique part of the story. Cite two excerpts from Torn from the Land where Barclay and Todd Lewan reveal their reporting process. Do you agree with their approach?

Review Stories from the Teacher’s Guide